Most people who work in local government are skeptical about its ability to accomplish anything. They essentially believe in governing by press conference – you announce that you are planning to do something, you allocate some resources, and you go on to the next thing. We know that change is possible. We’ve seen it happen. We’ve seen the quality of life in neighborhoods improve. We’ve worked on projects that have improved people’s lives. We want to write about the systematic obstacles to positive change in City government, as well as about what the conditions are for success.

But success is certainly the exception, rather than the rule. When we talked to state government about working in a senior level position several years ago , we were told by a remarkably frank public official, “Oh, you wouldn’t like to work here. We don’t do anything except hold media events.” An individual who is now a high profile elected official (who we will call Abagail Adams), and who was previously a senior aide to an even more high profile elected official (who we will call George Washington) once told us a story about that person. Adams told me, “I once complained to George Washington that all we did was hold press events – and we never actually DID anything. Washington said to me, Abby, when I hold a press conference, I AM DOING SOMETHING.” That story, told to us more than twenty years ago, has stayed with us.

We aspire to write, sometimes in real time, drawing on our thirty years of experience working around and in City government, about how that government works and doesn’t. We’re particularly interested in the ways in which “reform” systems put in place nearly one hundred years ago to prevent graft, fraud, patronage, self-dealing and incompetence in the numbingly boring areas of procurement and personnel, have become obstacles to good policy making and effective governance. Gigantic bureaucracies have grown up around these systems. Sometimes they are even weaponized by the most cynical public employees against those they want to hurt, either to advance themselves or simply out of spite or the sense of empowerment that lodging complaints about others provides. In addition, we like to quip that in any given year the amount spent on preventing waste, graft and fraud in City government has to exceed the amount wasted on waste, graft and fraud in the City’s entire history (leaving out the ten figure “City Time” scandal, which occurred DESPITE, these vast layers of supposed protections). The approval of contracts usually involves as many as a dozen approvals across a range of agencies – many, many hands checking off boxes along the way. Civil service protection is an insider’s game, that takes years to secure, and generally insulates the wrong people – while arbitrary personnel and policy decisions by high level appointees and life-time employees are routine.

More recently, elaborate land use and environmental processes have been established with the idea of increasing the level of engagement with and sensitivity to “community” concerns. Those processes were established very much in response to the destruction and over-reaching of “Power Broker” Robert Moses chronicled by Robert Caro and held up to analytical light by Jane Jacobs. Those regimes, also, have devolved into obstructionism and thoughtless box checking – having little to do with actual environmental protection or the protection of important minority, or even majority interests. ULURP and CEQR have taken on lives of their own, with huge enforcement bureaucracies focused on narrow requirements, losing sight of larger community values. Similarly, historic preservation (which admittedly has insufficiently large enforcement resources, creating a different set of problems) has lost its larger frame and fetishizes the old and engaged in inappropriate spot-zoning, often at odds with the city’s need for additional and affordable housing. A parallel regime of “public interest” litigation has also been weaponized as means for a small group of elite attorneys, using those regulatory schemes to exert un-democratic power over governmental decision making.

We know City government has the capacity both to provide quality services to New Yorkers and improve their lives. The City does an outstanding job providing high quality water to its residents. It reliably picks up garbage from residential buildings. The City’s robust and unique affordable housing programs were a key to New York’s renaissance beginning in the 1980’s. Entire neighborhoods in Brooklyn and the Bronx were transformed.

At the same time the City, for example, seems not to be able to maintain its public spaces. The Parks Department has been shown to find it difficult to execute capital projects on time or on budget. They City is widely recognized to be a terrible landlord at the New York City Housing Authority. While there has been some improvement in recent years, they City’s transportation policy remains insufficiently flexible and responsive to technological and social changes, like the need for bus rapid transit and light transportation alternative (like bikes and scooters, and the need for modern logistics and delivery systems). While some of the City’s schools remain among the best urban schools in the country, most students are underserved and segregated – and current policy nostrums threaten to disable even those excellent schools.

We want to use this forum to highlight the failures and successes in municipal service delivery, benefiting from the knowledge obtained both from working in the middle of the bureaucracy, as well in “partnership” with local government from the outside. Unfortunately, in our thinking about these issues over the last few years, we’ve identified more problems than solutions. We want to take advantage of the anonymity that this forum provides to be as forthright and clear as possible.

That said, many high-profile people in local government have struck us as being involved in public service to draw attention to themselves and to enjoy the exercise of power rather than to advance the public weal. Perhaps that statement seems naïve. Perhaps it appears overly cynical. We have also observed people in public policymaking who are truly dedicated to improving the lives of others. But, in writing here, we hope to criticize systems, ideas and ideologies – rather than individuals. Perhaps, occasionally, we will praise individuals who have taken risks and made change (where that can be done without an excess of self-revelation).

We recognize the dangers involved in setting ourselves up as the arbiter of the right and true, and the wrong and false. There is something inherently elitist and authoritarian about such an endeavor. But we will do our best to attempt to be fair, data-driven, discerning – and perhaps kind and generous as well in our writing. The systems constraining local government can and should be better.

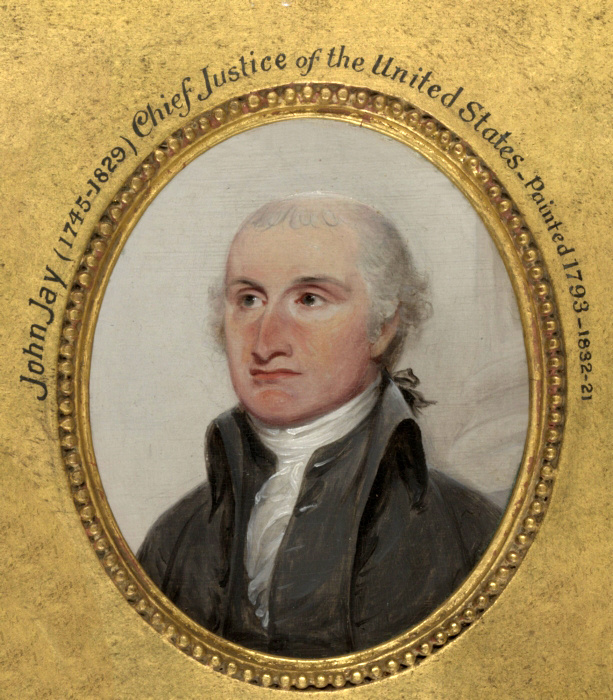

J.J.

Recent Comments