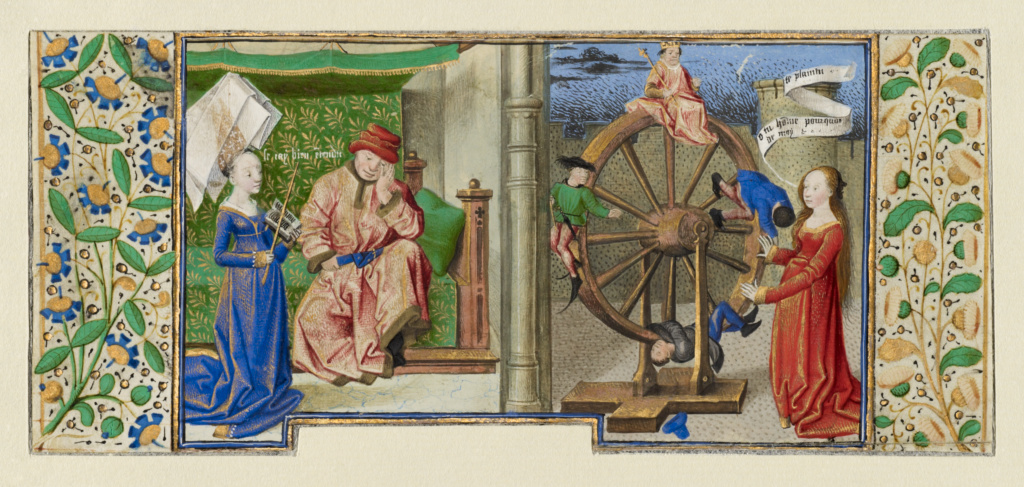

Fortune rota volvitur;

descendo minoratus;

alter in altum tollitur;

nimis exaltatus

rex sedet in vertice

caveat ruinam!

nam sub axe legimus

Hecubam reginam.

Underlying just about every issue effecting the functioning of City systems is the manner in which risk is handled. There is uncertainty involved in most, if not, all managerial decisions. We have to evaluate, in conditions of incomplete information, the likelihood of various outcomes, and the positive and/or negative consequences of those decisions. Sometimes, those probabilistic outcomes can be evaluated in monetary terms, and as a result, decision making is more straightforward. But often that it is not the case that the fiscal impact of decisions can be easily calculated. In the public sector negative political or reputational consequences of a judgment can be more important in decision making.

We would argue that flexibility, creativity and problem solving are essential to obtaining optimal public policy outcomes. What we most frequently find in City government is, first, a preference for doing things the way they have always been done, and a second, a preference for avoiding dealing with problems if at all possible. We have also observed that middle, and even senior, managers are generally discouraged from offering new ideas.

In the private sector, the evaluation of risk in the course of decision making can be much, much easier. Incentive systems are pegged to positive economic outcomes, either in the short or long term. The better those outcomes, the more reward to the decision maker or organization. Markets, theoretically, reward successful risk taking (and penalize bad bets). The institutional essence of capitalism, the financial markets, are supposedly all about rewarding correct calculations of risk. The public sector has no analogous meta-metric.

That being said, we have long wondered about the characteristic risk aversion among public servants. The avoidance of possible negative outcomes of any kind seems to be an essential part of most public decisions making. This has appeared to us as particularly odd, given that most public employees are insulated from negative sanctions by City personnel policies. There are elaborate processes in place, through civil service and otherwise, theoretically to prevent arbitrary personnel decisions. It is a stereotype about government that employees are difficult to fire or otherwise sanction. While these systems don’t protect elected officials and senior bureaucrats, those positions are only a small slice of public employment. In our observation, only very rarely is City employee negatively impacted by a bad business decision or for excessive risk taking.

So why is the taking of risk by public servants so seriously avoided? At the highest level, there is a culture among the media of exposing mistakes, without much analysis of the circumstances of the error. This is also a function of a rough and tumble competitive political culture, where there is benefit to elected officials, and the most senior appointed officers, seen in criticizing the mistakes of others. Good faith errors are not differentiated from egregious incompetence by even the respected broadsheet newspaper of record. Tabloid journalists seem particularly focused on publicizing errors. This might be a reason. But of the thousands of decisions made on a day-to-day basis by government workers, most are entirely unlikely to come to public attention. Those decicions just aren’t all that important. But even more mystifying to us is the lack of impact of the media on the public at large. No one really takes the reporting of the New York Postseriously, except for a small group of insiders – elected officials and senior bureaucrats. Post stories, for example, disappear quickly and generally have little to no effect on the voters at large – and yet a series of blistering Post stories, no matter how scurrilous or poorly reported, become part of an insider echo chamber that takes on a life of its own – with little resonance beyond the political class.

We have also observed that many elected and other senior public officials are principally focused on receiving positive media attention, even from the tabloids (perhaps, particularly from the tabloids) and are obsessively concerned about protecting their downsides from negative situations which might damage their future career prospects. As a result, they micro-manage their agencies, and demand that their subordinates take no risks at all – in order to avoid any possible negative outcomes. While this is a wide-spread practice, it is far from universal and in very large organizations, does not reach down all that far into the bureaucratic depths. There must be some other reason for the almost complete avoidance of risk by all City employees. We don’t regard the prior sentence as hyperbole. It is a precise statement of fact, in our experience.

An interesting example is the general risk avoidance of the policy administration of Mayor Bill DeBlasio during his last years in office. We have observed City Hall’s unwillingness to delegate authority and difficulty in making close decisions. We found this odd, given that the Mayor was not running for re-election and was unlikely to ever hold political office again. We might think that such a situation would provide fertile ground for bold initiatives and the testing of new policies and programs. There would be no political price to be paid by the Administration if any of these projects were to come a cropper. But City Hall continued to operate as if it were engaged in a reelection campaign, with continued fretting about how decisions might be received by the media, other elected officials and the public. It was if having been in campaign mode for the last two decades, since having been first elected to the New York City Council, the Mayor and his senior political and media advisors could not escape operating as if an election was imminent. As a result, opportunities for seriously addressing the kind of issues regarding equity and service to the disadvantaged, about which the Administration obviously cared, were not fully exploited.

The explanation for the broad phenomenon of local governmental risk avoidance, we have concluded, has to be that while government workers enjoy broad protections as to their tenure, no positive incentives are in place to promote risk taking within City government. There is no reward for those who carefully calibrate risk, proceed with something untried, and as a result improve government outcomes. The system is structured in such a way as to provide some negative consequences from failure, but no positive results from success. Obviously, there are no financial bonuses awarded for high performance, let along successful risk taking in government. Promotions within the bureaucracy come, generally not from high performance, but from length of tenure (primarily), ingratiation with decision makers (small “p” politics), and an absence of disqualifying blemishes on an employee’s record. As a result, a culture of risk avoidance permeates government service.

There are serious negative results from this systematic risk aversion. Change becomes more difficult to implement. Doing the same thing in the same way, no matter how dysfunctional, is simply easier. New ideas are difficult to suggest in a culture that discourages them and are nearly impossible to implement – unless they come from the top. This is a major reason why government is so often unresponsive and sclerotic. We have seen in government a failure to abandon obsolete practices, policies and even metrics, because there is no incentive for doing so, and often loud voices in opposition. With respect to metrics for example, we have seen City agencies insist on continuing to measure things that are no longer relevant (for example, because practices have so improved that the performance being measured meets standards and never varies). Data managers will refuse to alter the metric because “the data will no longer be comparable to past performance,” even though nothing useful is being measured.

This is not an unsolvable problem. A culture of intelligent risk taking could be encouraged at all levels of City government. We would suggest that for a Mayor or other senior City official to make a difference in the performance of local government that early in his or her tenure he or she very visibly reward a middle level manager for making an intelligent decision based on a careful analysis of risk – that didn’t pan out. This would send a message across government that implementing smart new programs will be rewarded – regardless of whether they work. The idea is to encourage flexibility and creative problem solving. Better decision making is more a question of leadership than it is of the establishment of new systems or processes.

The cost is low. In our experience when new initiatives haven’t been successful, the problems created are always relatively easy to solve. In fact, more often than not, even if the initial foray failed, the repair of the failure ultimately produces a superior outcome. Rarely do incorrect decisions as a result of flexibility or creativity in local public administration result in irremediable outcomes. Problems can be fixed. The benefit to the governmental outcomes of empowering managers to solve, rather than avoid, problems would be extraordinary.

Serious consideration needs to be given by thoughtful public officials to practices that support local public sector decision makers to find practical solutions to problems. While this sounds straightforward it would require radical cultural change in New York City government. Doing so requires a commitment to improving people’s lives through government and ignoring the noise created by short term carping competitors and the media. Encouraging risk in City government requires taking a long view that over time, aggerate outcomes of high-quality decision making will improve governmental results.

Recent Comments